# there are no Livonians

“There aren’t any Livonians,” that’s what I heard at the passport office when I went to apply for my first Latvian passport in the early 1990s and asked to have “Livonian” listed as my ethnicity – something that was illegal in the past. And the answer I got was: “if you want to get a Latvian passport at all, you have to give “Latvian” as your ethnicity.”

Last year when I was filling out some paperwork at an office, the assistant asked me: “How does that work – you’re a Livonian, but you’re a Latvian citizen?” Well, then I explained that the Livonians are indigenous to Latvia and so on. “Well, I sure haven’t heard anything like that,” she answered. Sure, because, after all, there aren’t any Livonians.

How could there be any? When I was in school, my history teacher said that the Livonians died out in the 13th century. Of course they did. Our villages and graves, our ancient fortifications are “Ancient Latvian” villages, graves, and fortifications.

Sometimes we’re told that these aren’t Livonian, because someone else lived there before the Livonians; or someone else lived there after the Livonians; or also that – we just don’t know what sort of nation the Livonians are, where they came from, and if they’re even a separate nation. Well, obviously, because there aren’t any Livonians.

And there also aren’t any Livonians in Latvia’s cultural history. A new book came out just recently and I went and looked. There aren’t any Livonians in there either. Not a word about how Christianity came to Latvia through the Livonians and that many Baltic German and Latvian culture workers – even today – have Livonian roots. Not a word that Livonian poet Jāņ Prints wrote and published poems in Latvian right after Blind Indriķis and before the first jaunlatvieši (New Latvians) came on stage. Not a word about how there have been nearly 40 Livonian writers, how there are Livonian composers and painters and other culture workers who are well-known in Latvia. Not a word about how the Latvian national anthem was written by the Livonian Baumaņu Kārlis or that the Latvian epic “Lāčplēsis” is a retelling of Livonian history and is set in all the places where the Livonians lived. But, after all, there aren’t any Livonians.

One could point out that the Livonians are described as an indigenous nation in Latvia’s laws, that these laws also say that it’s the state’s responsibility to care for the preservation and development of Livonian language and culture. But what’s a law after all? It’s a piece of paper, which is useful if someone starts asking questions – “see, it’s all right here in black and white, all our papers are in order.” But what do laws matter if there actually aren’t any Livonians?

Let’s take Latvia’s language law as an example. It says that Livonian is a language indigenous to Latvia, not some foreign language. And that Livonian must be used in the names of businesses and on road signs. But if I go to the business register and want to register a business name in Livonian, then I’m told that I can’t, because the name can’t include any Livonian letters. And when I’m being interviewed on national radio and want to have some Livonian music played, I’m told that I can’t, because it’s not in Latvian. Livonian can’t be written or heard, because there aren’t any Livonians.

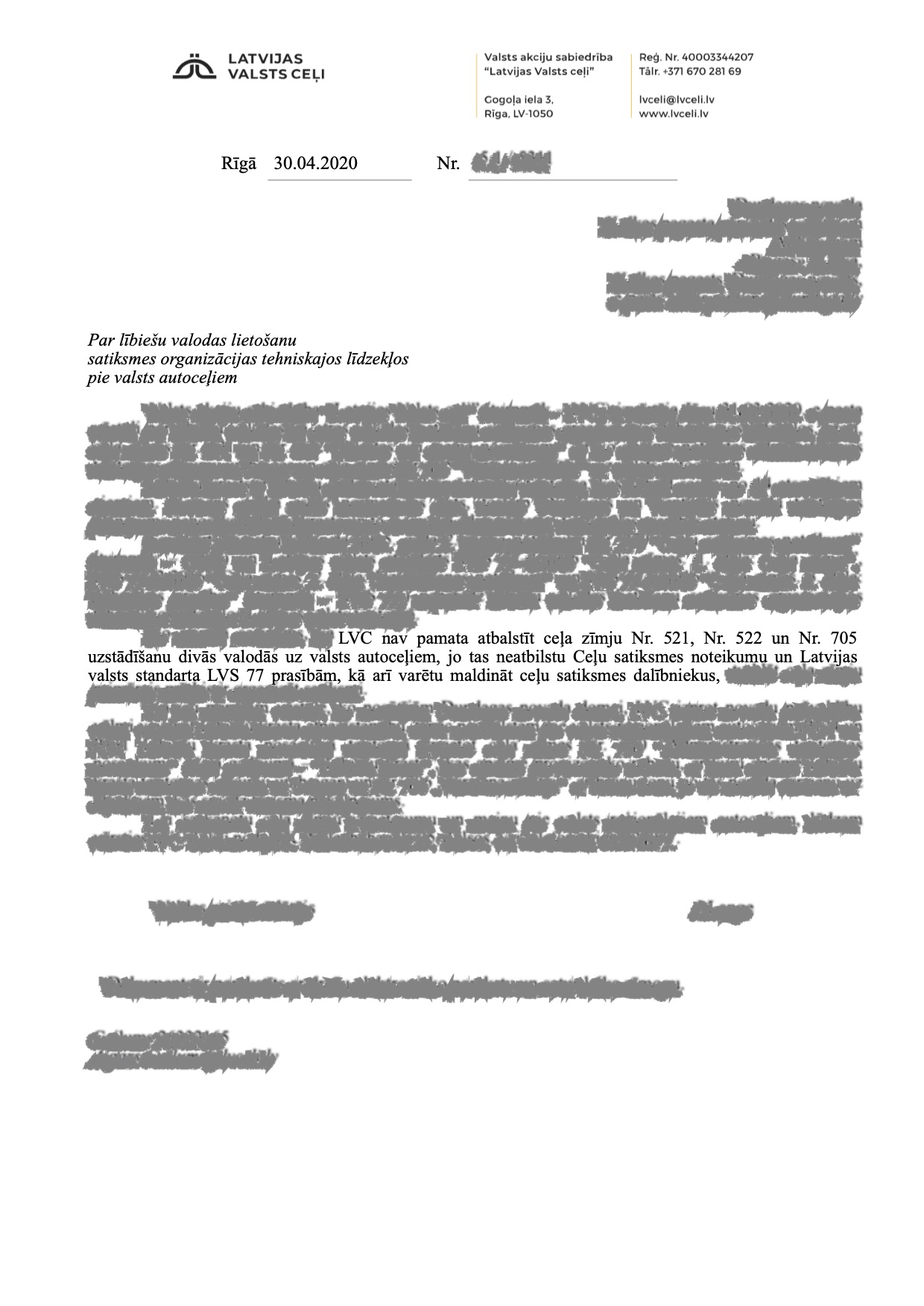

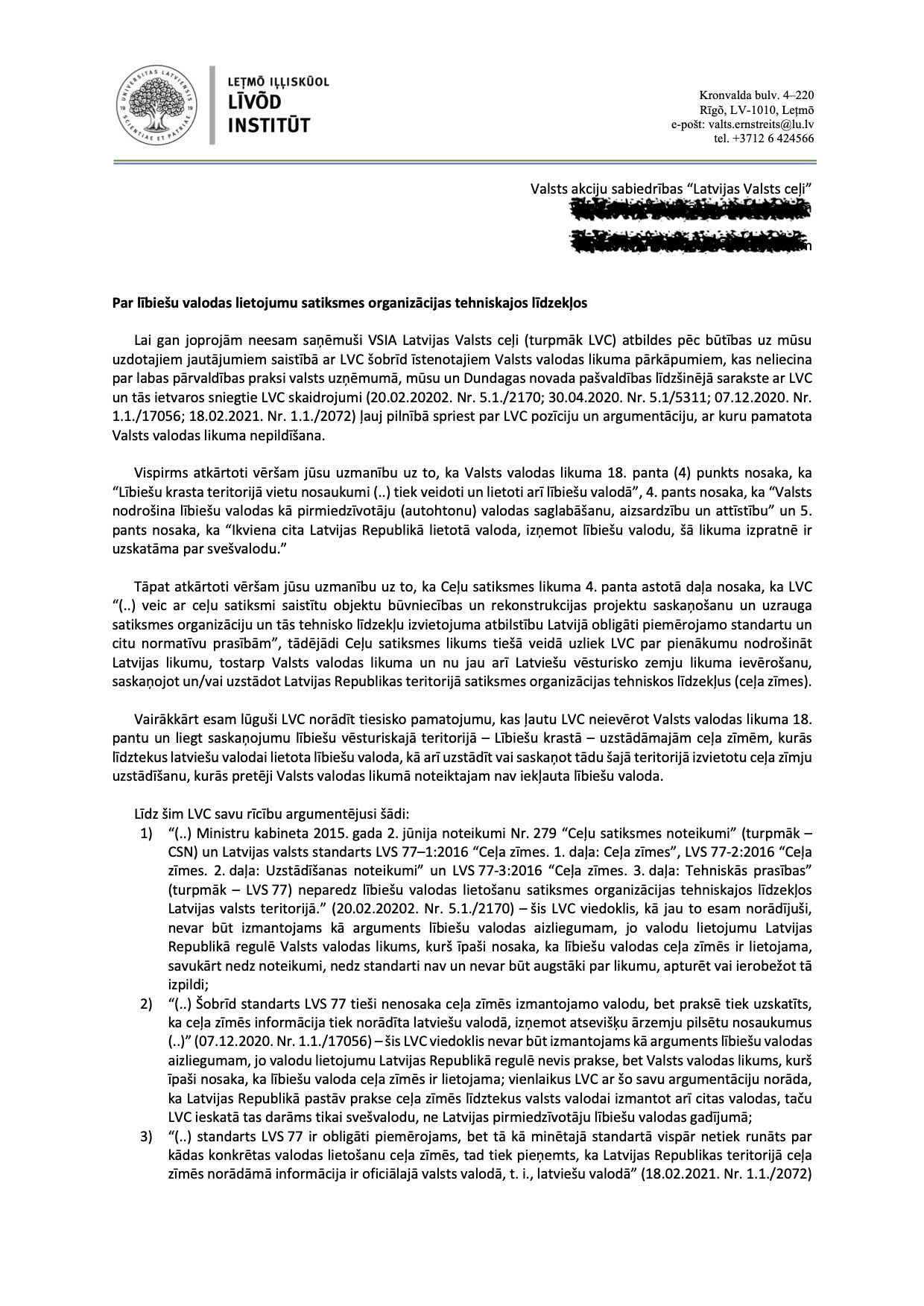

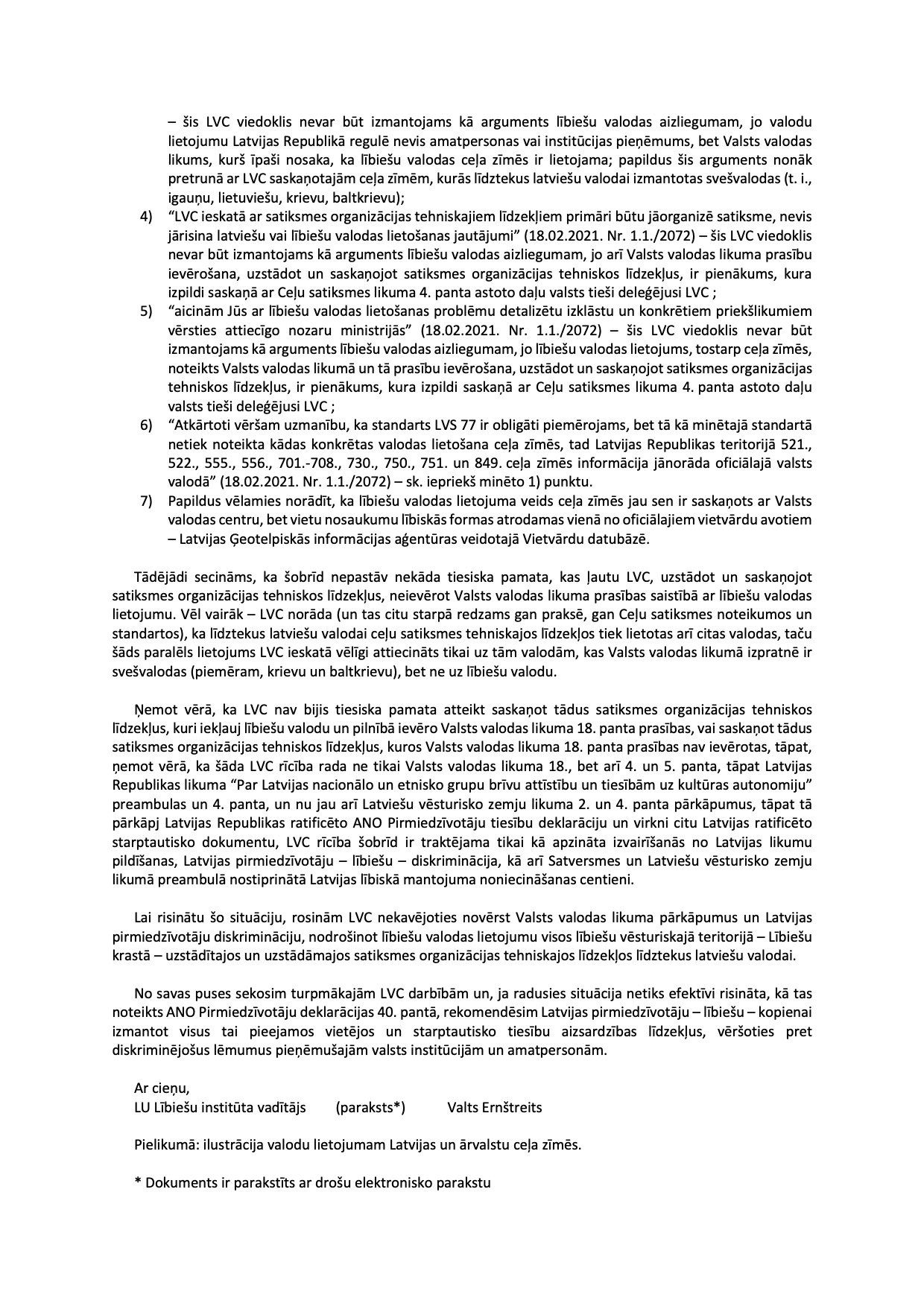

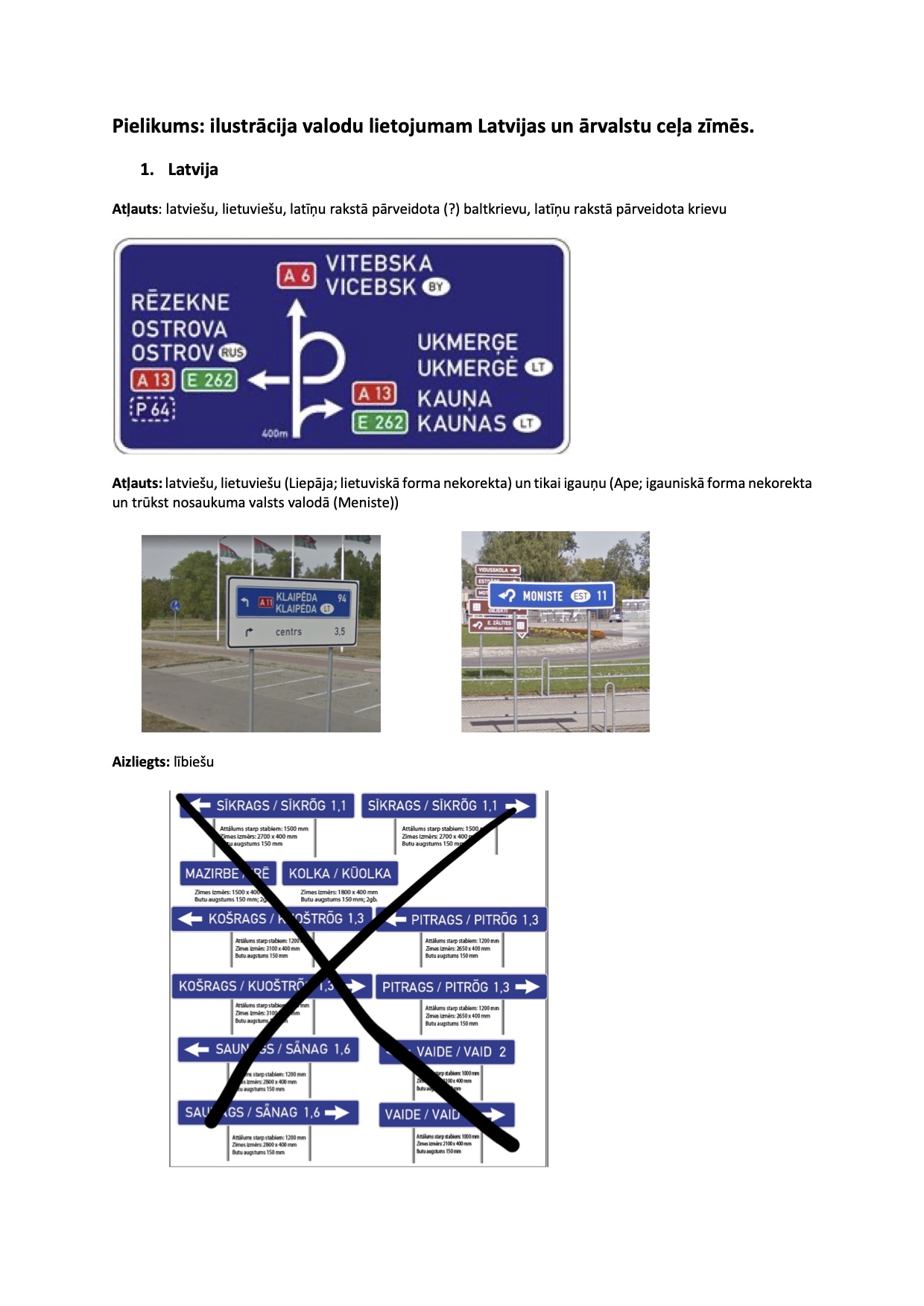

And when Dundaga municipality wanted to put up road signs in Livonian and Latvian, then Latvia’s main traffic bureau claimed that it wasn’t allowed. At first, they explained that traffic laws and standards don’t permit Livonian to be used – though these also doesn’t explicitly permit Latvian either. In reality, not only Latvian, but also Lithuanian, Estonian, and Russian are used on road signs (only Livonian isn’t allowed). Then they wrote that using Livonian might confuse people. Then they wrote that special letters – let’s say, Livonian letters – can’t be used, but Estonian and Lithuanian letters apparently can, as they are perfectly visible on the road signs put up by the traffic bureau. And then they wrote that the use of Livonian on road signs was, in their opinion, not a question of law but of practice, and that there was no practice for using Livonian in this way.

So, a law can say whatever you want. But if there’s someone sitting somewhere who thinks that there aren’t Livonians, then that law is for the birds. Because there aren’t any Livonians – that’s it, end of story.

It’s the 21st century. Latvia has been independent again for thirty years and it is also the Livonians’ only homeland and one that I too defended at the parliament building with a Livonian flag in hand in 1990.

Now I’m standing here on the Livonian Coast, in Pizā (Miķeļtornis), on my ancestral land. Near the cemetery where my family and their neighbours lie – Livonian poets, caretakers of culture and language, and those who struggled for Livonian rights over many generations. The cemetery where the first monument to the Livonians was built in the dark 1970s – a monument, which like the Livonians themselves, is invisible, because no signs point to its location. In a village whose Livonian name can’t be shown, because there aren’t any Livonians.

I’d like everyone to have the chance to spend a moment here. To reflect on themselves and their own nation. To think about how it is when day after day your nation is removed from books, signs, and history, when your language can’t be shown in your own country, in your homeland, when every day you’re forced to watch and listen as your language and nation are erased.

“You’re not Livonians. The last Livonian died, I know, I read it somewhere,” is something that’s said from time to time. I look in the mirror and see myself, I see that I’m not dead – I’m speaking, breathing, thinking.

Replace “Livonians” with your own nation’s name. How does that feel? Is that better? Are you starting to feel like you’re in a cage and that others are pointing and taking pictures of you, but that you’re actually not in there at all?

Replace “Livonians” with your own name.

Right now, the cage is empty. Because there aren’t any Livonians.

Now it’s your turn to take their place.